Randall's Plaque: The Hidden Trigger for Kidney Stones

Randall’s plaque is at the heart of calcium oxalate kidney stone formation. This hidden lesion inside the kidney acts like a magnet for stone crystals. In this blog, I break down what Randall’s plaque really is, how it forms, and the simple step you can take to prevent it from causing kidney stones.

Key Takeaways

-

Randall’s plaque is harmless until exposed to calcium oxalate crystals.

-

Supersaturated calcium and phosphate trigger plaque formation.

-

Stones grow by binding to plaque at the tip of the renal papilla.

-

Eliminating dietary oxalate is the most effective prevention strategy.

If you’ve been suffering from calcium oxalate kidney stones, you may have heard of the term Randall’s plaque at some point. But what exactly is it? And what role does it play in kidney stone formation?

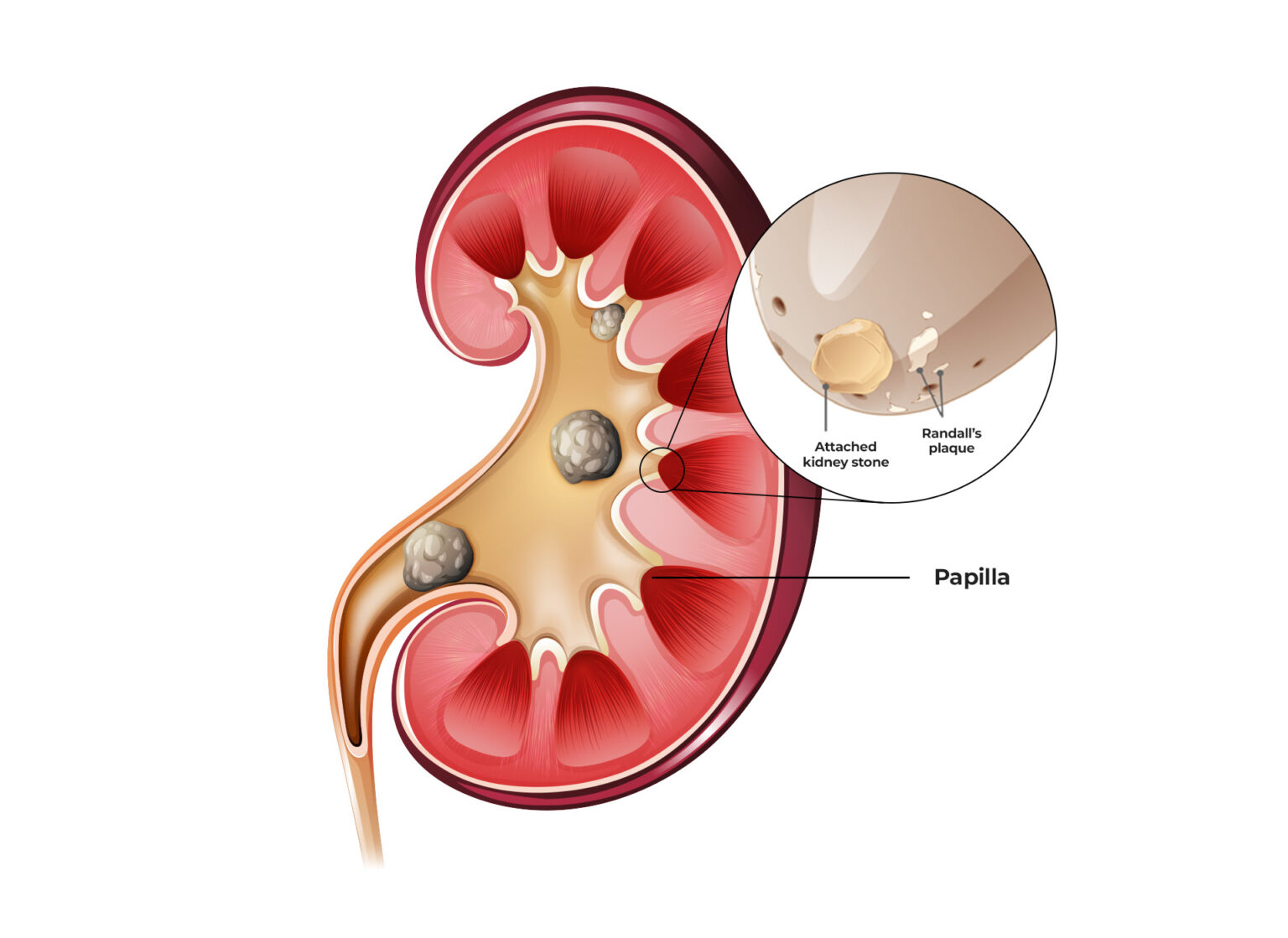

Randall’s plaque is a lesion that develops inside the kidney. It sounds scary, but it’s really just a byproduct of supersaturated calcium and phosphate ions. These minerals deposit on the inside surface of the kidney, especially at the tip of the papilla (the small pyramid-shaped structures in the kidney).

Over time, these deposits can range from a few millimeters to covering the entire tip of the papilla. Randall’s plaque becomes the anchor point where calcium oxalate kidney stones start to form.

Interestingly, people who don’t even form calcium oxalate stones can still have Randall’s plaque. It’s also found in people with other types of stones like uric acid stones or even those who’ve never had a kidney stone at all. We’ll talk more about why that’s important later.

How Randall’s Plaque Forms

Now that you know what it is, let’s dive into how Randall’s plaque actually forms inside the kidney.

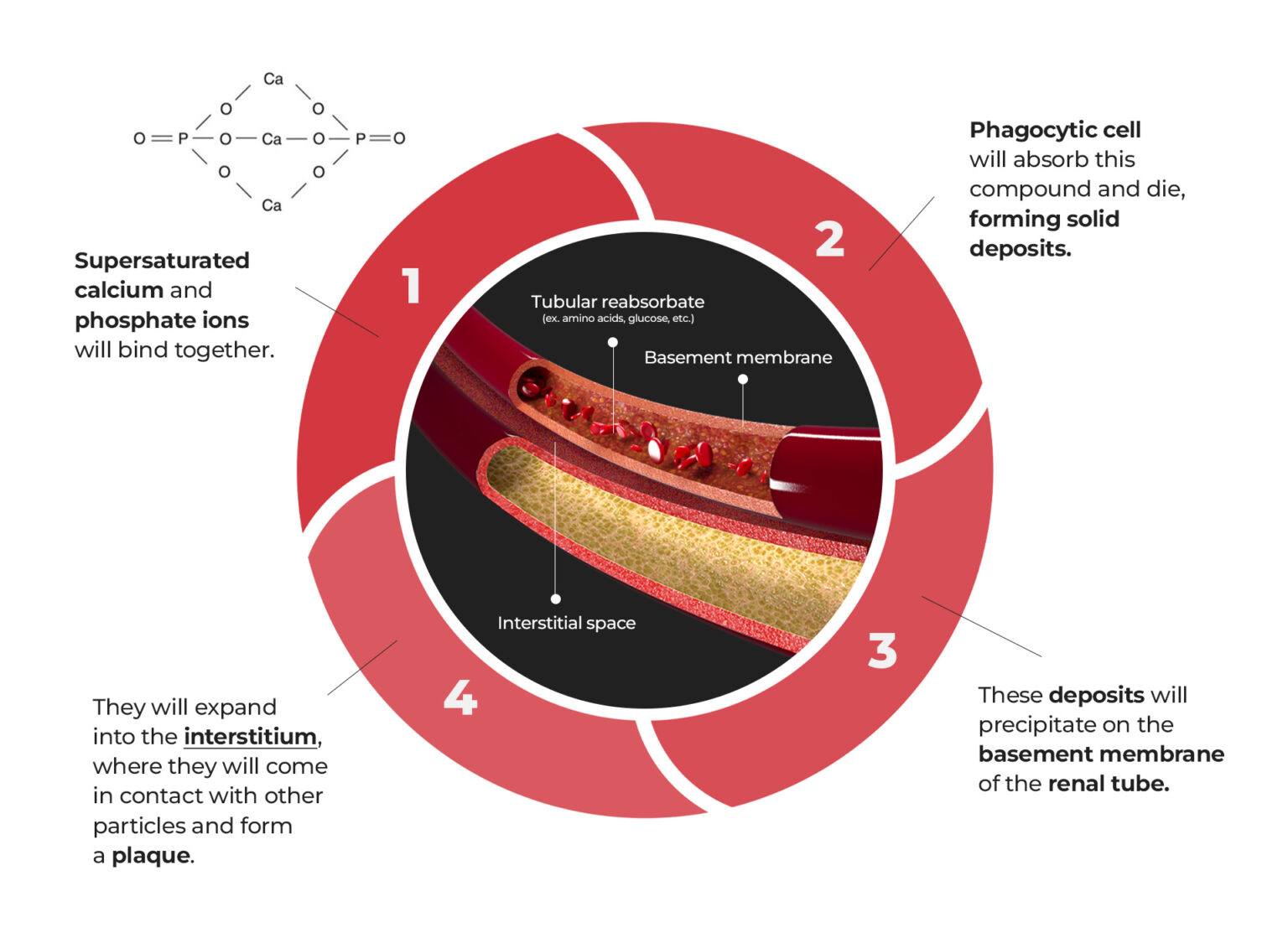

It all starts with supersaturation of calcium and phosphate ions in the urine. Supersaturation simply means there’s too much of a substance to be dissolved. Think about mixing a powdered drink into water — if there’s too much powder, it settles at the bottom. That leftover powder is a perfect example of supersaturation.

When supersaturated calcium and phosphate are present in the kidney:

-

Phagocytic cells (a type of immune cell) attempt to digest the excess minerals.

-

These overloaded cells eventually die, leaving behind solid deposits.

-

The deposits migrate into the renal tubules, the kidney’s filtration units.

-

From there, they expand into the space between the tubules and blood vessels (called the interstitium).

-

Finally, they make contact with the urine at the tip of the papilla.

At this point, the plaque is in place. But remember — on its own, Randall’s plaque is harmless. It only becomes a problem when it meets calcium oxalate crystals.

🛒 Check Price & Purchase Stone Relief Pass AM/PM Bundle on Amazon

How Kidney Stones Form on Randall’s Plaque

The plaque itself doesn’t hurt you. It just sits there — until calcium oxalate crystals come into contact with it.

Here’s the typical progression of calcium oxalate stone formation on Randall’s plaque:

1. Nucleation

This is where calcium and oxalate ions in the urine find each other and bind. When they combine, they create a solid crystal. This is the starting seed of a future kidney stone.

2. Growth

These tiny crystals travel through the kidney and eventually land on the Randall’s plaque at the papilla. Once attached, they begin growing bigger and bigger in the presence of more supersaturated calcium and oxalate.

3. Aggregation

As crystals grow, they start to clump together. Think about rock candy — tiny sugar crystals sticking together to form bigger structures. That’s what’s happening with your kidney stone at this stage.

4. Detachment and Stone Formation

Once enough crystals accumulate, the growing stone can eventually detach from the papilla. Sometimes stones stay tiny. Other times, they grow to enormous sizes. Why a stone detaches when it does is still somewhat of a mystery — it could be physical movement, pressure, or changes in the chemical environment.

Without Randall’s plaque acting as a platform, calcium oxalate stones would have a much harder time getting started.

🛒 Check Price & Purchase Stone Relief Pass AM/PM Bundle on Amazon

What You Can Do About Randall’s Plaque

So now you might be wondering — if Randall’s plaque is the root cause of calcium oxalate stones, how do you get rid of it?

Here’s the thing: You don’t need to eliminate Randall’s plaque. You just need to make sure it never encounters calcium oxalate crystals in the first place.

And the most effective way to do that?

Stop consuming oxalate.

Without oxalate in your body:

-

Calcium oxalate crystals can’t form.

-

No crystals = no binding to plaque = no kidney stones.

This is the simplest and most powerful step you can take if you form calcium oxalate stones. And remember, forming these stones isn’t random. If you have them, it’s because your body lacks the genetic ability to properly process oxalate. Somewhere in your ancestral past, you didn’t develop the machinery needed to handle plant-based toxins like oxalate.

Today, that shows up as stone formation when you eat foods high in oxalate. Your body doesn’t know what to do with it, so it dumps it into the kidneys — and the cycle begins.

One caution:

Even a “low oxalate” diet may not be enough for some people because oxalate is cumulative. Your body holds onto it longer than you might think, and it can take time to clear it out completely. Intake and output aren’t balanced.

If you’re serious about preventing calcium oxalate stones, it’s not about “moderating” oxalate.

It’s about eliminating it.

No oxalate = no crystals = no kidney stones.

🛒 Check Price & Purchase Stone Relief Pass AM/PM Bundle on Amazon