Understanding Calcium Oxalate Dihydrate Kidney Stones

Calcium oxalate dihydrate kidney stones are a weaker, less dense subtype of calcium oxalate stones, making them easier to break apart and pass naturally. In this blog, I explain the different variations, causes, and strategies for managing these stones without surgery. Learning this key difference changed my entire approach to kidney stones—and it could change yours too.

Key Takeaways

-

Calcium oxalate dihydrate stones are less dense and easier to break apart.

-

These stones are primarily caused by diet and elevated calcium levels.

-

There are three main subtypes with distinct shapes and formations.

-

Understanding your stone type can dramatically change your treatment plan.

When most people hear about calcium oxalate kidney stones, they don’t realize there’s a weaker, less dense subtype that could make all the difference in treatment. Calcium oxalate dihydrate kidney stones are unique because they’re much easier to break apart and pass naturally—sometimes even without the need for surgery.

What Are Calcium Oxalate Dihydrate Kidney Stones?

Calcium oxalate dihydrate stones are a weaker subtype compared to the calcium oxalate monohydrate stones. The difference comes down to their structure. Dihydrate stones have two water molecules for every one calcium oxalate molecule. This extra water makes the stone less compact and less dense, meaning it’s easier to break apart.

In contrast, monohydrate stones have a tighter one-to-one structure, making them harder, denser, and much more difficult to pass naturally.

Just like their denser cousins, dihydrate stones are tied to secondary hyperoxaluria, which means they are driven by dietary choices, not genetic malfunctions. This means we have more control than we think.

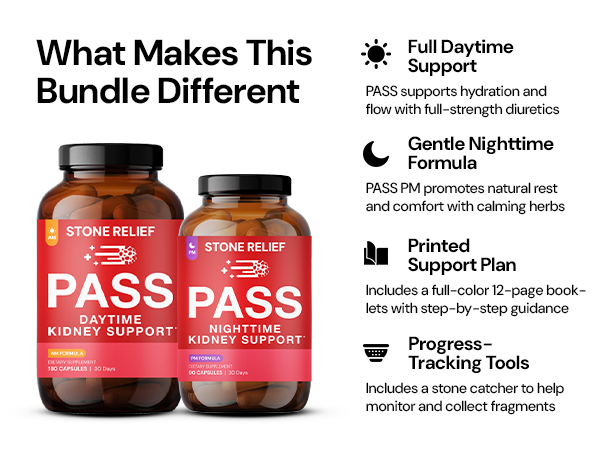

🛒 Check Price & Purchase Stone Relief Pass AM/PM Bundle on Amazon

Key Contributors to Calcium Oxalate Dihydrate Stones

The main driver of these stones is elevated calcium levels—a condition known as hypercalciuria. When calcium in the blood gets too high, it favors the formation of dihydrate stones instead of monohydrate ones.

Other contributors include:

-

Vitamin D sensitivity, which can influence calcium absorption.

-

Hyperparathyroidism, which disrupts calcium regulation in the body.

-

Low water intake, leading to concentrated urine and easier crystal formation.

Now that we understand the basics, let’s dive into the different subtypes of calcium oxalate dihydrate stones.

Calcium Oxalate Dihydrate Type 2a Stones

The type 2a stone is the most common dihydrate subtype. It has an oblong shape and forms along the walls of the kidney. Unlike the round shape of most monohydrate stones, these stones grow longer because they adhere to flat surfaces inside the kidney.

The most painful characteristic of type 2a stones is their sharp, spiky surface. When I passed my first nine-millimeter calcium oxalate dihydrate stone, it felt like passing barbed wire. If I hadn't created a natural product to break it apart, the process would have been unbearable.

Type 2a stones are primarily caused by high calcium levels in the blood. This shifts the crystallization pathway away from monohydrate formation toward dihydrate structures.

🛒 Check Price & Purchase Stone Relief Pass AM/PM Bundle on Amazon

Calcium Oxalate Dihydrate Type 2b Stones

The type 2b stone is the second most common and has some noticeable differences. These stones are generally rounder and feature long, smooth crystal formations that spiral around the stone.

Researchers often compare the appearance of type 2b stones to a desert rose, though the resemblance is a bit of a stretch.

Just like type 2a, these stones have sharp edges and a light yellow to light brown color due to their less dense molecular structure.

Contributing factors include:

-

Elevated calcium levels (hypercalciuria)

-

Low urinary citrate (hypocitraturia)

-

Low urine output (stasis)

The longer these stones sit in the kidneys without being flushed, the more unique their structure becomes.

Calcium Oxalate Dihydrate Type 2c Stones

The type 2c stone is extremely rare and looks very different from the others. These stones often appear lumpy, resembling cauliflower more than a typical crystal.

Their color is usually pale brown to gray-beige, and they form under more extreme circumstances. This subtype usually indicates a malformative uropathy, meaning there’s some kind of physical abnormality or obstruction in the urinary tract that slows urine flow dramatically.

Without enough urine flow to wash away stone-forming elements, these unique stones grow over time into their distinct, cauliflower-like shapes.

If you recognize stones like these, it’s critical to discuss the possibility of underlying urinary tract issues with your doctor.

🛒 Check Price & Purchase Stone Relief Pass AM/PM Bundle on Amazon

Why Stone Density Matters

Calcium oxalate dihydrate stones are not only easier to pass naturally, but they can also be broken apart with the help of herbal products.

When I first faced 30 kidney stones between my two kidneys, I knew surgery wasn't the answer for me. Instead, I created a natural supplement that helped dissolve these weaker density stones over time.

Because dihydrate stones have a looser structure, consistent hydration and herbal support can greatly increase your chances of passing them safely and avoiding surgery.

How Long Does It Take to Pass a Dihydrate Stone?

In my experience, and based on feedback from thousands of others, calcium oxalate dihydrate stones can often be passed within weeks to a few months.

Stones actively passing through the urinary tract typically dissolve faster due to the higher velocity of urine flow, while stones sitting in the kidney may take longer because of less turbulence.

The key is to remain consistent with hydration and any natural remedies you’re using. Patience and persistence are crucial.

Final Thoughts on Managing Calcium Oxalate Dihydrate Kidney Stones

If you recognize that you’re forming calcium oxalate dihydrate kidney stones, you’re in a good position. These stones are easier to manage than the denser monohydrate stones.

By understanding your stone type and making the right dietary changes, increasing hydration, and using a targeted natural approach, you can potentially avoid surgery altogether and take control of your kidney health for good.

If you’re serious about putting an end to your kidney stones, understanding this information is the first step toward lasting freedom.